National Geographic Traveler has just posted its top 20 best things to do in cities around the world this summer. Here are mine, in reverse order:

20. Stockholm, Sweden Have a tour of the recent riots, taking in some great ethnic food along the way. Take the blue (T11) metro line to the northern suburb of Husby. Then top it off with a spot of nude sunbathing at Ågesta Beach (bus 742).

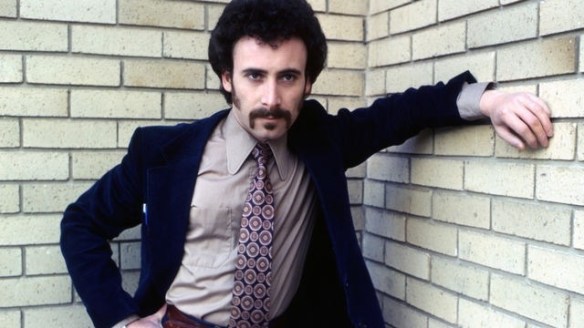

19. New York, United States Take a trip back in time on the famous New York subway, unchanged in 40 years. Has the US completely lost it? It’s 1973 down there. Lou Reed’s chewing gum, spat out as he left the Velvet Undrground’s session for Loaded in 1969, still visible at Spring St. station, SoHo.

18. Singapore, Singapore Play hide and seek with your kids in the smog (but do wear masks). Plenty of time left to do it: it’s going to last for weeks. Have a drink on the veranda at the Raffles Hotel afterward.

17. Edinburgh, Scotland Tour the the never-ending tram works on Princes St. Are they building it – or taking it to pieces? Your guess is as good as ours. Later on, take the Scottish DNA test courtesy those latter-day eugenicists at http://www.scotlandsdna.com/. Are you pure enough for Scotland?

16. Madrid, Spain Help remove the shanty town at El Gallinero, Madrid. Let’s clean this place up! Take the train to Collado Villalba, and get a cab from there. Great tapas back in Madrid. Try El Museo del Jamon, nr. Puerta del Sol.

15. Tehran. Iran Try a spot of flag-burning in Azadi Square to celebrate the election of President Hasan Rowhani (but not the Iranian one!). Check out the street food: ‘Mexican Corn Cup’ and boiled beets, available everywhere.

14. Doha, Qatar Visit the new Taliban Embassy. If you can find it. They’ve removed the sign.

13. Moscow, Russia Stand up for traditional family values in an anti-gay demonstration. Plenty of choice, free to participate. Then frozen vodka with Moscow’s jet set at Simachev’s, Stoleshnikov Lane.

12. Shanghai, China Take a refreshing dip in the Huangpu River. Watch out for pigs!

11. Paris, France Ever wanted to try your hand at being an air traffic controller? Now’s your chance. France routinely stops air traffic during the summer to let tourists have go at guiding planes – but without the risk, because they ground them all. Try Paris Charles de Gaulle. It’s popular, though – be prepared for long queues.

10. Venice, Italy Biennial festival of Garbage. The mysterious Biennale attracts pilgrims from all over the world to worship displays of rubbish, and speak in mystical terms, guided by the enigmatic catalogo, a religious text. The origins of this rubbish-worship are obscure.

9. London, England Re-enact the spectacular looting of summer 2011. Just take a train to Clapham Junction (every five minutes from Waterloo), head for the Debenhams department store, and help yourself to whatever you like. Nobody minds. That buccaneering spirit is London’s gift to the world.

8. Detroit, United States Celebrate the city’s culture-led revival with a visit to the opera house. Free entry.

7. Toronto, Canada It’s party time – and boy, do Torontonians know how to let it all hang out. How about sharing a crack pipe with the city’s Mayor?

6. Limassol, Cyprus Check out the spectacular ruins of Europe’s banks, strangely compelling in the sunshine. Great Russian food.

5. Kabul, Afghanistan Model aircraft fans! You’ll think you’ve died and gone to heaven. Actually…

4. Brasilia, Brazil How about some free-running (parkour) on the government buildings of the Monumental Axis? Very popular this summer. Watch out for teargas, though. Then try some authentic Lebanese kibbeh in the Bar Beruite, Asa Sul. Open late.

3. Athens, Greece Learn the ancient art of the moutza in Syntagman Square. Careful what you do with it once you’ve learned.

2. Istanbul, Turkey Meet the friendly local police at Gezi Park.

1. Sao Paulo, Brazil This summer’s hit. Where to start in the South American metropolis? A quarter-million-strong demo on the Avenida Paulista? Check. Blocking the main highway to Santos? Check. Looting of shops and banks? Check. It’s all to play for in summer 2013’s hottest destination.

Here’s the National Geographic’s selection: http://intelligenttravel.nationalgeographic.com/author/iheartmycity/